HISTORY

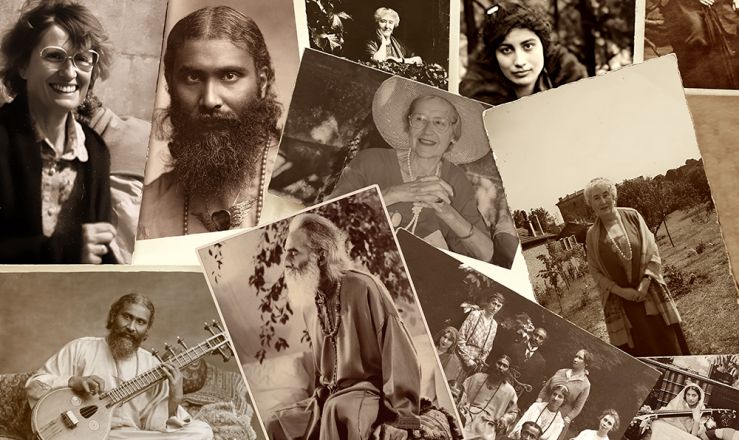

The Healing Order in Murshid’s Time: Ancient traditions and contemporary influences

‘Healing’ as a subject is introduced in the autumn of 1916 among the lectures for the year’s course given by Pir‑o‑Murshid from October to the following June and July, the weekly lecture to be held on Wednesdays at 4.30 pm. This continues up to and including the springtime of 1917, but is omitted from October 1917. In 1917 ‘Character Building’ lectures are replaced by those on ‘Moral Culture’.

By that time, Halima Jane Reynolds is in charge of the subject of ‘Moral’, in the role which is later described as ‘Authorised Representative’ for a certain specialized subject or activity. Upon the move to Gordon Square in January 1920, her description becomes: ‘Secretary of the Healing Group’, which means that she is in charge of it.

Meanwhile, by springtime 1916 ‘Eastern Magnetic Treatment’ was begun by Murshid Ali Khan. The reports were that ‘The curative results of his treatment have been marvellously successful... ‘. He was apparently encouraged to do so by the example of ‘Brother Ramananda’, who from Hampstead offered ‘Present or Distant Divine Healing’.

Murshid Ali Khan had an authorization for healing from his teacher in Baroda known as Bhaiyaji (Revered Brother). It is really striking that Murshid Ali Khan took an initiative in practise which then was taken up as a teaching theme by Murshid half a year or so later!

In Murshid’s paternal ancestry there was a tradition of Turkestani‑Central Asian bakhshes. A bakhshe is more or less the same as a shaman: incantation, healing, ‘magic’ that later continued as music, meditative healing and mysticism.

The ancestry’s earliest, Central Asian Turki descriptions are those of yuzkhan and bakhshe, the ‘horde’ ‑ chieftain and wise men or patriarchs.

Escaping from Tamerlan’s devastations in the 14th century, ultimately they arrived in India, settling in the Punjab as landowners. Yuz, meaning ‘horde’, suggests nomadism, but they must have settled in Turkestan already, for a real horde would have rather joined than fled from Timur!

Anyway, this horde must have produced a superabundance of bakhshes, since one reference to them used to be bakhsheane yuz, meaning horde of the bakhshes. From bakhshe they became mashaikhan (as ascetics or mystics), their kinship chiefs from yuzkhans ‑ Jum’ashah (or Mirkhel = group chieftain). Again, Yuzkhan Khasset in India with time became ‘Yuskin Caste’ ‑ with mysticism, music, and adab‑ādāb (gentlemanly ways of attitude, behaviour and standards) as their caste dharma.

Of course, healing practices are widespread in India and all over the Orient and elsewhere, but a personal tradition would always mean a stimulus!

Halima, Mrs Jane Reynolds, may have been motivated by the example of Christian Science. At the time it was supposed that Murshid’s third, American, wife, was related to Mrs Baker Eddy: Murshid speaks appreciatively of Christian Science in Biography.1 But now it would seem that not she, but Murshid Ali Khan developed an interest taken over by Murshid.

No trace (as yet) of Mrs Reynolds after Murshid’s departure from London in 1920! Murshid wrote that, ‘Differences among my loving friends threatened our Movement with a breakdown and caused the removal of the Khankah to Geneva.’2

It seems in London there was a split between the more Anglican and the more Theosophic Sufi workers, also glossed as one between the more bourgeois and the more aristocratic members. Only Kefayat LLoyd was very High Church and aristocratic.

The worst split was between Zohra Williams and Sharifa Goodenough, and the former left totally disgruntled. Other non‑theosophists must have done likewise and that would explain Mrs Halima’s absence along with no few others, of recurrent appearance during the six London years of Murshid and his family.

The Theosphizers cast Murshid in the ‘World Teacher’ role that Annie Besant expected of Krishnamurti. Therefore they interpretted the Sufi ‘Message’ as expressing what today we would call a ‘neo‑religion’.

Thus they sought renewal of religion along messianic‑avataristic lines; exactly the opposite of what Murshid intended. His vision was of a modern, immanentist mysticism for the secular world‑to‑be approached, in addition to philosophic contemplation and esoteric practice (jnana and rajya yogas, haqiqat and ryazat), by aesthetic absorbtion: music, beauty, realisation in ever‑deepening ‘human and divine’ realization.

Healing after 1921 was taken up again by Kefayat LLoyd, who replaced an earlier Christian Science idea with an emphatic Anglican orientation. Thus, Murshid Ali Khan’s and Murshid’s meditative ‘spiritual healing’ became a typical prayer or faith healing, yet of course (like Murshida Green’s ‘Universal Worship’ and Murshida Goodenough’s hierarchical reconstruction of the Sufi Order) permeated with Murshid’s ideas and ideals as expressed in all his priceless teachings.

Mahmood Khan

February 2010

References:

———————————————————————————————

1Biography of Pir‑o‑Murshid Inayat Khan, London and the Hague: East‑West Publications, 1979.

2Biography page 149.

‘Healing’ as a subject is introduced in the autumn of 1916 among the lectures for the year’s course given by Pir‑o‑Murshid from October to the following June and July, the weekly lecture to be held on Wednesdays at 4.30 pm. This continues up to and including the springtime of 1917, but is omitted from October 1917. In 1917 ‘Character Building’ lectures are replaced by those on ‘Moral Culture’.

By that time, Halima Jane Reynolds is in charge of the subject of ‘Moral’, in the role which is later described as ‘Authorised Representative’ for a certain specialized subject or activity. Upon the move to Gordon Square in January 1920, her description becomes: ‘Secretary of the Healing Group’, which means that she is in charge of it.

Meanwhile, by springtime 1916 ‘Eastern Magnetic Treatment’ was begun by Murshid Ali Khan. The reports were that ‘The curative results of his treatment have been marvellously successful... ‘. He was apparently encouraged to do so by the example of ‘Brother Ramananda’, who from Hampstead offered ‘Present or Distant Divine Healing’.

Murshid Ali Khan had an authorization for healing from his teacher in Baroda known as Bhaiyaji (Revered Brother). It is really striking that Murshid Ali Khan took an initiative in practise which then was taken up as a teaching theme by Murshid half a year or so later!

In Murshid’s paternal ancestry there was a tradition of Turkestani‑Central Asian bakhshes. A bakhshe is more or less the same as a shaman: incantation, healing, ‘magic’ that later continued as music, meditative healing and mysticism.

The ancestry’s earliest, Central Asian Turki descriptions are those of yuzkhan and bakhshe, the ‘horde’ ‑ chieftain and wise men or patriarchs.

Escaping from Tamerlan’s devastations in the 14th century, ultimately they arrived in India, settling in the Punjab as landowners. Yuz, meaning ‘horde’, suggests nomadism, but they must have settled in Turkestan already, for a real horde would have rather joined than fled from Timur!

Anyway, this horde must have produced a superabundance of bakhshes, since one reference to them used to be bakhsheane yuz, meaning horde of the bakhshes. From bakhshe they became mashaikhan (as ascetics or mystics), their kinship chiefs from yuzkhans ‑ Jum’ashah (or Mirkhel = group chieftain). Again, Yuzkhan Khasset in India with time became ‘Yuskin Caste’ ‑ with mysticism, music, and adab‑ādāb (gentlemanly ways of attitude, behaviour and standards) as their caste dharma.

Of course, healing practices are widespread in India and all over the Orient and elsewhere, but a personal tradition would always mean a stimulus!

Halima, Mrs Jane Reynolds, may have been motivated by the example of Christian Science. At the time it was supposed that Murshid’s third, American, wife, was related to Mrs Baker Eddy: Murshid speaks appreciatively of Christian Science in Biography.1 But now it would seem that not she, but Murshid Ali Khan developed an interest taken over by Murshid.

No trace (as yet) of Mrs Reynolds after Murshid’s departure from London in 1920! Murshid wrote that, ‘Differences among my loving friends threatened our Movement with a breakdown and caused the removal of the Khankah to Geneva.’2

It seems in London there was a split between the more Anglican and the more Theosophic Sufi workers, also glossed as one between the more bourgeois and the more aristocratic members. Only Kefayat LLoyd was very High Church and aristocratic.

The worst split was between Zohra Williams and Sharifa Goodenough, and the former left totally disgruntled. Other non‑theosophists must have done likewise and that would explain Mrs Halima’s absence along with no few others, of recurrent appearance during the six London years of Murshid and his family.

The Theosphizers cast Murshid in the ‘World Teacher’ role that Annie Besant expected of Krishnamurti. Therefore they interpretted the Sufi ‘Message’ as expressing what today we would call a ‘neo‑religion’.

Thus they sought renewal of religion along messianic‑avataristic lines; exactly the opposite of what Murshid intended. His vision was of a modern, immanentist mysticism for the secular world‑to‑be approached, in addition to philosophic contemplation and esoteric practice (jnana and rajya yogas, haqiqat and ryazat), by aesthetic absorbtion: music, beauty, realisation in ever‑deepening ‘human and divine’ realization.

Healing after 1921 was taken up again by Kefayat LLoyd, who replaced an earlier Christian Science idea with an emphatic Anglican orientation. Thus, Murshid Ali Khan’s and Murshid’s meditative ‘spiritual healing’ became a typical prayer or faith healing, yet of course (like Murshida Green’s ‘Universal Worship’ and Murshida Goodenough’s hierarchical reconstruction of the Sufi Order) permeated with Murshid’s ideas and ideals as expressed in all his priceless teachings.

Mahmood Khan

February 2010

References:

———————————————————————————————

1Biography of Pir‑o‑Murshid Inayat Khan, London and the Hague: East‑West Publications, 1979.

2Biography page 149.